Around 9:30 p.m. on Thursday night, a room full of guests gathered around two TVs on the 17th floor of New York’s Public Hotel, waiting impatiently for Anna Delvey to solve the ICE app’s technology issues and video-chat into her first solo art exhibit. While the artist, née Anna Sorokin, couldn’t be there in person — the convicted scammer, who spent two years in prison after swindling New York’s elite out of thousands of dollars, is currently being held at an ICE detention facility in Orange County after overstaying her visa — that hasn’t stopped her from staging her comeback.

The show, a one-night-only event titled “Allegedly,” comes on the back of Delvey’s return to the public eye thanks to Netflix’s TV show loosely based on her life, Inventing Anna. The night started in one of the hotel’s dark lounge rooms, which was comfortably crowded by the time I arrived at 7:45. Clubby music blared while bartenders poured wine and Champagne. The majority of guests seemed to be press, though I bumped into two friends of the DJ, a Danish documentarian whose friend worked at the hotel, and a few distant acquaintances of Christopher Martine, the curator responsible for getting Anna’s drawings out of the ICE facility. Martine, who organized the event, told me that Julia Fox and Julia Garner — who played Anna in Inventing Anna — were supposed to attend but were “in L.A. and Europe,” respectively.

Though the event was billed as an art show, there was no art immediately visible, and I was not alone in wondering whether, much like Delvey’s claim earlier that day that she was starting a law firm, this was all one big stunt. But after a brief dance number by drag queen Yuhua Hamasaki impersonating Delvey (she exited with the words, “The wire is coming!”), I heard someone behind me say, “Excuse me.” I turned to see a model wearing black sheer pantyhose pulled over her head and huge Fendi sunglasses holding a gold-framed 9-by-12 drawing in front of her chest, elbowing her way through the crowd. More art-carrying models followed, strutting down a runway-esque path crowded with oblivious partygoers who seemed unconcerned with getting out of the way.

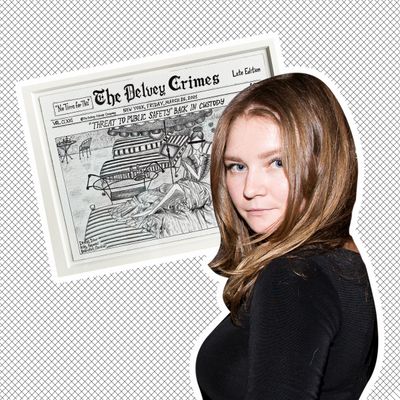

Delvey’s pencil drawings fall somewhere between fashion sketches and New Yorker cartoons, labeled in careful script with captions like “I am the show” and “Never complain, never explain.” Martine tells me they paid lawyers to retrieve the drawings, which were made in detention, and when that got too expensive, they used the prison mail system, mailing only on days when “people within the facility that she trusted” were working. They seem intended as a commentary on her circumstances over the past few years, though the takeaway is not always clear. In Vanilla Ice, Delvey has drawn herself surrounded by a sea of ICE detainees with the words “White privilege application status: denied” written along the bottom. Another piece, Trial Is the New Sex Tape, depicts a recreation of her trial, featuring her signature white dress and black choker.

After the show, the crowd was instructed to make its way upstairs to a bland, gallery-like space dotted with cocktail tables where Delvey’s drawings were displayed on foldout tables at the edges of the room. Scannable QR codes on plaques offered links to purchase a percentage of the original collection or drop $250 on a print. The only art-world representatives I met were two social-media strategists from Christie’s. Asked about Christie’s interest in Delvey’s collection, they replied, “Nothing right now.”

Eventually I ran into someone who had actually crossed paths with Delvey, model and casting director Livia Rose Johnson, who informed me that multiple people in the room were texting Anna as we spoke. They might have been the cluster of middle-aged white men in business suits, who stuck out among the designer belly shirts and chic silk co-ords dominating the room. One of them, who appeared to be a member of her legal team, delivered a rousing speech while we waited for Anna to “arrive,” in which he emphasized that “she could become a free person any day she wishes” and was bravely staying in the U.S. instead of going home to Germany (he did not explain why). His toast ended with several “Free Anna!” chants, which were picked up by more than a few fans in the room.

Finally, the guest of honor made it to the video call, easily recognizable in her Celine glasses, yellow detention jumpsuit, and blurred background. In a short interview conducted by a boisterous blonde woman who went unintroduced, Delvey told the crowd about planning the show and using dull rubber instruments available in prison to create the sketches.

Delvey’s grift has always included vague artistic aspirations. Much of the money she was eventually convicted of stealing was purportedly intended to fund a “dynamic visual-arts center” that she called the Anna Delvey Foundation — which, of course, never materialized. Apparently, that has not swayed her confidence or determination. On Thursday, she declared, “My Anna Delvey Foundation will definitely be realized.” Martine spoke about her work with esteem, recalling that she took “maybe five times as long” as she initially told him she needed to create the collection but that “the work speaks for itself.” Yet her fans appeared less interested in the art than in Anna herself. At one point during the interview, someone in the back of the room shouted, “Anna, are you on Raya?”

Between the logistical blunders and deeply bizarre fangirling, the night felt a lot like the haphazard existence described by Anna’s old New York acquaintances, who watched the fake German heiress bounce from hotel to hotel with unkempt hair and slapdash designer clothes. The public knowledge that Delvey is a fraud hasn’t stopped her from drawing a crowd or throwing a giant hotel party full of models with designer sunglasses. Even from ICE detention, Delvey packed a room with well-dressed people transfixed by her every move.