It was one thing for Antonio Reynoso, then a city councilman campaigning for the Brooklyn borough president gig vacated by Eric Adams, to say he would do everything he could to help improve maternal-health outcomes. It was another thing for Reynoso to have to call up the leaders of the major local institutions who are used to receiving millions in capital funding from the BEEP’s office — the Brooklyn Academy of Music, the Brooklyn Museum, the Brooklyn Botanic Garden — and tell them they would get nothing this year. To his relief, few balked. It helped, Reynoso says, that “they were all run by women, most of ’em run by Black women. And they’re like, ‘Don’t worry about us one bit. We’ll see you next year.’” One unnamed organization seemed doubtful, he adds, until he really did give every penny of his $45 million budget to pregnancy care at Brooklyn’s three public hospitals.

Reynoso, 40, speaks thoughtfully, deliberately, and less like a politician than a community organizer who knows how to take the temperature of the room. His awakening began in 2017, when his wife, Iliana, was pregnant with their first child. Unsatisfied with the care they were getting at a private hospital in Manhattan — “They had us in and out. If it was ten minutes, it was a lot. And we didn’t feel comfortable asking questions. There were no midwives,” he says — they found what they were looking for at Woodhull Medical Center, right in his own district. He knew that Woodhull’s checkered reputation, especially for its emergency room, wasn’t entirely unwarranted. He had gone himself a few times growing up in Williamsburg for stitches and emergency care. But midwives were familiar to both of them, if indirectly: Reynoso’s father had been born at home on a farm in the Dominican Republic.

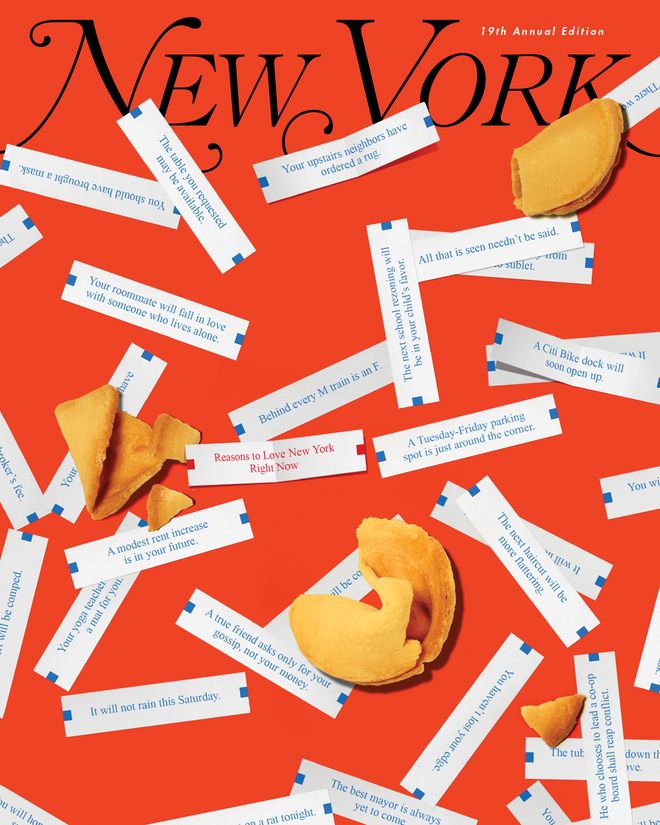

Cover Story

By chance, their first appointment was with Helena Grant, who was then the director of midwifery at what she had renamed the Labor and Birthing department (because delivery implies a passive birther) and is now president of the state organization New York Midwives. What would have been ten minutes in Manhattan became a one-hour conversation. “And through that, she found out I was the local councilmember,” Reynoso tells me. “And she’s like, ‘Oh, I need to talk to you.’” At their second visit, Reynoso says, Grant asked him, “‘Do you know anything about maternal health?’ And I was like, ‘I know it’s not good, but I don’t know much about it.’ And she said, ‘Do you know your wife is nine times more likely to die during childbirth than a white woman?’” To be clear, that’s in New York City, where the racial disparity is far worse than the one nationwide. The city doesn’t publish mortality data by hospital, but Woodhull itself has been the site of some of the most visible tragedies, each occurring out of the purview of the midwives: Sha-Asia Semple died in 2020 after a botched epidural at the hands of an anesthesiologist who later lost his license, and this November, protesters gathered outside the hospital following the death of Christine Fields, who’d had an emergency C-section.

Reynoso’s lessons continued at every prenatal visit, he recalls: “Do you know they think Black women have a pain threshold that’s higher? Do you know that coagulation is a historical health complication for Black women that they don’t account for?” He tells me he has worked his whole life to never feel like things were hopeless; he has seen himself as someone who is always fighting, who could show up and fix something. “But knowing that I can’t beat nine times the rate, right? I can’t beat that disparity, that inequality, as a husband sitting next to my wife.” They came back to Woodhull for the birth of their second son, too.

“I told Ms. Grant this: ‘If I ever have the power or the influence or the resources to be able to combat this crisis, I would,’” he says. Once in office, “I could have given $5 million to these public hospitals and made a difference at the margins and been able to claim that I helped maternal health,” he adds, fixing me with a direct gaze. “Then I would be doing exactly what everybody does in this business. They did the bare minimum to say they did something and didn’t effect meaningful change.”

What does this money get? Among other things, renovations on NICUS, labor and recovery rooms, and a state-of-the-art birthing center. It also seems to get Mitchell Katz, who runs New York City’s public-hospital group, Health + Hospitals, to take Reynoso’s calls. One day, he called to complain that Kings County Hospital had only one midwife. “I had just given them how much? Eighteen million dollars to Kings County, or something like that, out of the $45 million,” Reynoso says. “I’m saying, ‘I feel very uncomfortable with that. I just gave all this money, and there’s no midwifery services.’ Katz called me two hours later, and he said, ‘Helena Grant will be coaching seven new midwives, and they’ll be working very soon in Kings County.’” Reynoso is looking over renovation plans and critiquing initiatives he thinks are too modest. Says the borough president, “I want these to be places where somebody from Spain is like, ‘We got to go have our baby in Brooklyn.’”

More reasons to love new york

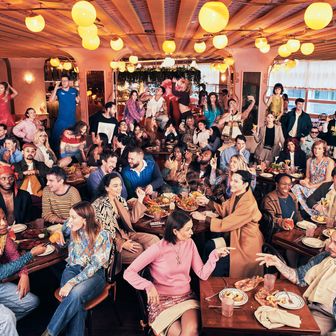

- We Took New York’s TikTokers to Lunch

- The Dare Loves to Write Songs About Sex

- The Hancock Is the Party House of Bed-Stuy