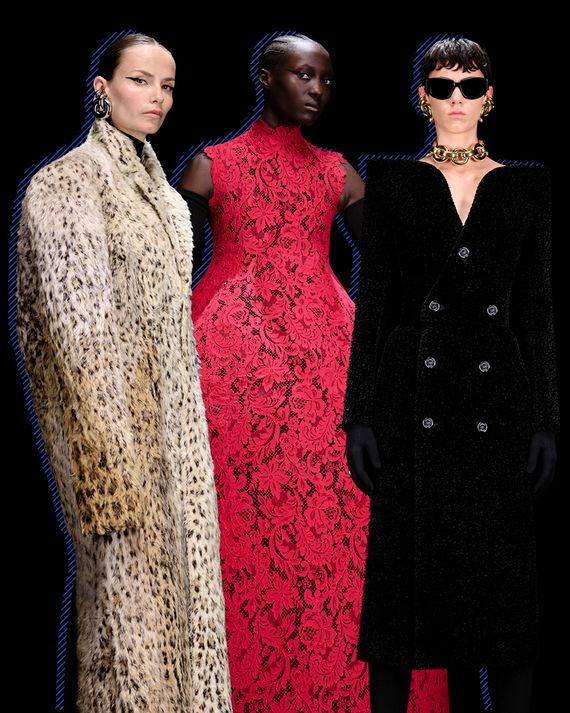

No one would call Demna’s fall couture collection for Balenciaga — the 52nd of the house — casual or accessible. A gown worn by Eva Herzigova, consisting of 10,000 hand-mounted, hand-stitched crystals, can be yours for half a million euros. Some jeans are not really jeans, but rather oil-on-canvas paintings, the work of a team of artists that takes around two months to produce the pieces for a single pair. A plush coat in the cream-and-brown spots of a snow leopard is not exactly a fake, either. Its fur is embroidery.

Traditionally, in couture, a bride closes a show. On Wednesday, however, the artist and Balenciaga regular Eliza Douglas came out in a dress of armor, 80 pounds of gleaming, custom-fitted metal, and carrying a white carnation — a reference to Joan of Arc, the French teenager who, dressed as a man and carrying a white banner, rode into battle against the English, saving her country. At 19, she was burned at the stake for heresy.

Answering reporters’ questions, Demna said, “Somehow this last look signifies that making clothes is my armor. That’s what I do best and that’s what I will always do.” He added that the costume was also a way to “create this bridge from the past til now, which is one of the reasons I wanted to do couture in the beginning.”

Then a writer asked, “How can couture be contemporary?”

“I think you just saw it,” Demna replied.

The question itself is telling of the industry. Continuing, he said, “We live in an industry that is, unfortunately, in a critical state, I believe. Because it’s full of fake creativity and a kind of impostor fashion. It’s really inflamed. Couture, to me, is the only way to shed light on the essence of this job: making real clothes, authentic creativity, the importance of the person who wears it, and not the endless marketing and selling, and all this blah-blah that has cannibalized the whole industry. My job is to show that. It’s like anti-virus. Couture is like Moderna. It cannot save it, but it can at least highlight the importance of keeping its immunity. For me, without that, there is no hope.”

Many of the clothes offered this week at the Paris couture show are certainly luxurious and flattering, and we’ve seen all kinds of embellishments. But shouldn’t couture be more than that — that is, more than an exercise in luxury and fantasy, or, God knows, respectability? Until the Balenciaga collection — which is Demna’s third since the company restarted couture in July 2021, after a gap of roughly 50 years — there has not been a feeling of modernity.

And what characterizes that feeling? For starters, it should suggest a connection with the past. What made Demna’s first couture show so awe-inspiring that the room fell completely silent was that he married his ideas, the stuff he had been working on since he arrived at the brand in 2015, with the forms of Cristobal Balenciaga. You could finally see where Demna was going with his bulky and austere shapes, and why, also, the Spanish couturier, born at the end of the 19th century, was a modernist ancestor.

On Wednesday, in the newly expanded couture salons on Avenue George V, he seemed even more free to explore the legacy. He opened the show with Danielle Slavik, who modeled for Balenciaga in the 1960s and who wore an identical copy of a dress he first designed in 1966, a black velvet gown with a string of pearls stitched into its shoulders and looping down the front and back. But there were other evening dresses that simply evoked the authority of Balenciaga, like a long, belted “robe de chambre” in black silk satin and lace that looked cool in profile, thanks to some volume in back, and a pink satin, side-draped gown on the Russian actress Renata Litvinova. As usual, the cast was a mixture of ages and genders, modeling all-stars like Herzigova and Ines de La Fressange; actresses, notably Isabelle Huppert; and new people. In contrast to most other brands, his models look highly individual, even odd. But that too is modern.

The other important way that Demna suggested modernity was by making familiar shapes — jeans, a tailored suit or coat — in common materials or with techniques that have in a sense been repurposed. For example, a men’s suit was not made of Prince of Wales wool, as it appeared to be (even at close range). Instead, it was made of denim woven in a checked pattern. Just as with the painted pieces or the embroidered faux fur, the workmanship and level of detail were astonishing. But the point is when you combine everyday things with fairly standard techniques — albeit, executed extremely well — you get a tension. In short, you don’t really understand what you’re looking at.

And maybe that’s why the writer naïvely asked the question: “Can couture be contemporary?” The answer was staring at her.

Demna considers everything, and that’s surely a mark of haute couture. He evolved his tailoring, reducing some of the bulk in the shoulders. He added some striking jewelry: a chunky gold-plated link bracelet and fat gold ear clips, with an extra, smaller gold ring you can add higher on the ear. Though the selection is small, it’s the best new jewelry offering since Phoebe Philo’s pieces at Celine. (Balenciaga put the jewelry, as well as a few garments from the show, in its George V boutique for immediate sale. The bracelet is 10,000 euros.)

The music was also different this season and telling of the kinds of things that run through Demna’s mind, as well as those of his creative team. Normally, his husband, the composer Loik Gomez, also known as BFRND, creates the show’s music. This time, however, he worked with two AI programs and some sound engineers to make a soundtrack of Maria Callas singing alone — that is, without the sounds of an orchestra. The result was something achingly pure.

“Perfection is not reachable,” Demna explained of his choice of Callas, adding, “Cristobal Balenciaga always looked for that perfection, in everything. He put in a sleeve, he took it out. He would never be a hundred percent happy. I think the voice that has talked to me the most in my life is Maria Callas.”

And without the orchestras, it was a little bit imperfect and thus human.