Pierpaolo Piccioli called his Valentino couture collection “Un Château,” which is pretty funny, given that the location was Château de Chantilly. Some designers have a genius for finding paradox in a castle tower, a moat. Piccioli said he liked the idea of showing simple clothes in “a place where rules were once important.” Maybe, but you can’t exactly erase the image of a castle in a drone shot anymore than you can ignore the fact that the international superrich are back in force. This week, many were passing through Paris — stopping at couture houses, jewelers — before going to the south of France, or Italy, or their yachts for the summer.

The rest of us peons were on the road to Chantilly, a 90-minute trek from Paris in a rush hour. That’s another thing that seems to mock Piccioli’s fantasy of simplicity and calm and humanity gathered by the moat at sunset: the sheer cost of getting people there, not just several hundred guests but also models, dressers, photographers, caterers, security guards, and the staff of Valentino’s ateliers in Rome. The decision to show on the grounds of one of Europe’s most spectacular castles begins to make sense. The payoff in terms of images is huge.

Some years ago, Piccioli put Valentino on a new path of gorgeous colors and lighter, almost minimalist designs, a look that bridged Valentino glamour with the realities of contemporary life. In the interim, he has occasionally swung hard back to the sequins and frills, as he did in January for a night-club-themed show and later for a silly ready-to-wear collection. He had no explanation for the shift to simplicity beyond, “I feel it’s more right for this moment.”

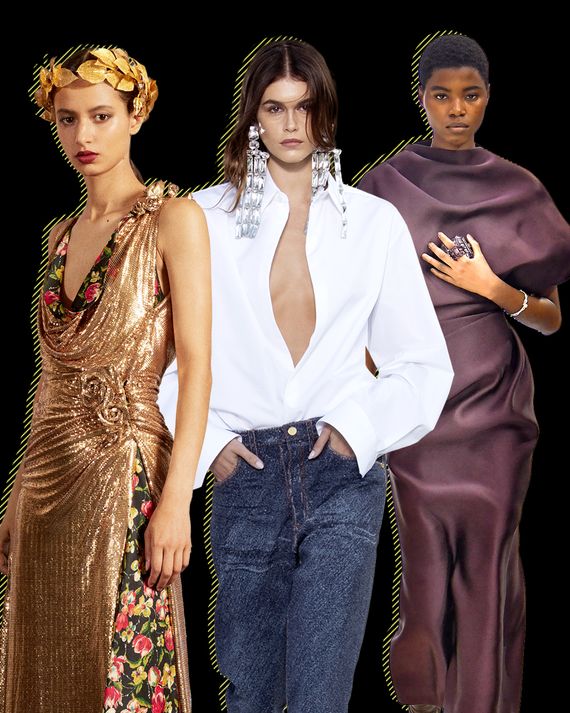

So it seems. Kaia Gerber opened the show in an oversize white cotton shirt and a pair of blue jeans, embroidered with thousands upon thousands of tiny beads to mimic the texture and hues of denim. One of the next looks out on the long, snaking catwalk was essentially a T-shirt in creamy white cashmere. You pop it over your head more or less; what you can’t see is the sheer inner structure, a kind of corset, that holds the dress (and you) in place and allows the fabric to do its thing — that is, flow. Piccioli did a number of styles like that in hard-to-pinpoint shades of gray, lilac, and pink. Also in the same casual-glam mode were caftans, loose coats with a hint of high-church pomp, and some terrific prints that were like pop abstractions of baroque patterns.

Although the collection didn’t quite have the thunder of his original color explosion, and hooded stoles also looked secondhand, its timing was spot on.

“Last season, we sold as many couture dresses as we could sell,” Fendi’s Kim Jones told me. “It’s so easy to wear.” His clothes are also relatively simple, or maybe deceptively simple, but one difference between Fendi and many other houses is the degree of finesse seems higher. That’s true of the workmanship, the quality of the fabrics, and, above all, the choice of colors. Jones has one of the best eyes for color in the industry, evident in the light emerald and mellow ruby satin chosen for a pair of draped dresses. There’s no way you could achieve those cuts, fit, and finishing outside of haute couture, and Jones leaves no room for doubt.

At the same time, there’s a pragmatism at work. Couture is a dressy business these days with a big marketing purpose; long gone are the days when houses would offer private clients a full wardrobe. Giorgio Armani and Alexandre Vauthier, both of whom had excellent shows, stuffed their collections with dressy trousers and jackets, and Armani, using a lot of Chinese red and heritage patterns, offered the kind of slim-fitting, unimpeachably pretty gowns that actresses will like, especially at awards season. But Jones was one of the few designers this week who thought to include short, so-called cocktail dresses in the line. Expertly draped, without adornment, they looked great.

Another thing I liked was how he used the corset, if you can call the taut central panel in some of his dresses. It added an athletic feel without losing the overall polish of the clothes. The collection marked the launch of the brand’s fine-jewelry line, designed by Delfina Delettrez Fendi. Hence the jewel palette mixed with earth tones, the tiny jewel-box clutches, and a modest scattering of embellishing, including crystals on a bisque-colored coat made of feather-cut shearing and a suit beaded all over with fat pink stones and worn with one of Delettrez Fendi’s diamond collars. The suit, Jones said, was inspired by a pair of leggings once owned by the artist and fashion icon Leigh Bowery.

Julien Dosena, the latest guest designer at Jean Paul Gaultier, went in the opposite direction, as you might expect of a house that got its impudent outrage from the subculture. And isn’t that where most good ideas in fashion come from? (Well, at least until lately.) Last season, Haider Ackermann took a decidedly high-fashion stance at Gaultier, with models throwing poses. Dosena, the designer at Paco Rabanne, who was about 8 years old when he first saw Gaultier on French TV, based his vision on the street, and on some landmark shows, including “Rabbi Chic,” and then brought the seating close to the runway so that the models were practically touching the guests.

It was a solid collection, with jaunty pinstriped tailoring, some artful uses of Paco chain mesh, a gorgeous archival lace and embroidered blouse with a feathered gray pencil skirt, and the requisite jabs at what remains of propriety (if anything), like sheer slip dresses with an embroidered full bush.