This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

It’s Karl Lagerfeld Week in New York. A Bunyan-size head of the designer looms near the escalators at Bloomingdale’s, and he’s in the windows at Bergdorf Goodman. Considering all the fuss around the reopening of the Tiffany store on Fifth Avenue, it’s almost remarkable that someone at LVMH didn’t think of a tie-in — with Karl Golightly. LVMH also owns Fendi, where Lagerfeld worked for 54 years.

Tonight, at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, there’s the ghoulish prospect of famous people going in KL drag — that is, in sunglasses, high-collared black-and-white ensembles with dandyish neckties and a sprinkling of jewels, maybe a powdered ponytail or two. A self-declared caricature, Lagerfeld is getting his own freak parade. The reason is the opening of the exhibition “Karl Lagerfeld: A Line of Beauty,” which kicks off with the Met Gala. The first thing guests will see upon entering the exhibit, which was designed by the architect Tadao Ando, are the black-gloved hands of Lagerfeld rapidly sketching clothes, taken from videos projected on a long curving wall. Also at the entrance is one of his many desks, set with his characteristic clutter of paper, books, and art supplies. Maybe somebody will pour out a Coke Zero in a goblet. So the props are in place.

Want more of the Met Gala? Sign up for The Cut daily newsletter so you don’t miss any of our coverage. Newsletter readers will also receive exclusive interviews with attendees and Cut staffers’ personal picks for the best — and worst — looks of the night.

And now here’s the paradox: “A Line of Beauty” is far less concerned with the man and the myth than the work he produced over his seven-decade career. We all know that Lagerfeld was a tremendous worker — “lots of class but working class,” he often said, only half joking. He had to be disciplined to design for multiple houses at once. When he joined Chloé and Fendi in the mid-1960s, he had already worked for Balmain and Patou, both old-line couture houses, and he continued to ghost-design for other labels. During the years 1992 to 1997, he made collections for Chanel, Fendi, Chloé, and his own line. Today, designers are free to jump between brands or collaborate with fast-fashion companies, and the reason is Lagerfeld. He invented the idea of a designer as a free agent, a hit man. And he did so at a time when the convention was against him. I remember Pierre Bergé, who was Yves Saint Laurent’s partner, beefing in the ’90s that Lagerfeld would never be a major influence since he didn’t have a couture house in his name and his designs always changed. That’s what a lot of people thought back then. Not anymore, of course.

Since his death in 2019 at age 85, Lagerfeld has been the subject of several biographies, including William Middleton’s Paradise Now, published this year, and two movies are in the works: one starring Jared Leto and the other, Kaiser Karl, a six-part Disney+ series, starring the German actor Daniel Bruhl (All Quiet on the Western Front) and set mainly in the ’70s. The interest is understandable. Lagerfeld was a fascinating man, partly because he was a bundle of contradictions he didn’t care to resolve. “I like to look very superficial,” he told a writer in 2007, in a typical stroke of wit and deflection. He also made the houses he worked for, above all Chanel, very profitable. But his fashion legacy has been overshadowed by his lifestyle and late-career celebrity, which began in 2004 with his H&M collection and ran a parallel course with the rise of social media.

Complicating matters further are the cracks he made about people, often to do with their physical appearance. I adored Lagerfeld. No one was funnier, warmer, and more generous with his insight. He was one of the few designers who was confident enough to allow reporters to sit in his studio and watch the work unfold. Still, for all that, I never skipped down the steps at Chanel after such an encounter without glancing at a mirror to see if a knife wasn’t planted in my back.

As with the blockbuster McQueen show, which the Met put on a year after his death, Andrew Bolton, the museum’s chief costume curator, didn’t want to wait for Lagerfeld. “Maybe it’s wrong,” he said, “but I always worry that when you leave something too long, revisionism will creep in. The authenticity becomes slightly altered if you leave it for a long period of time.”

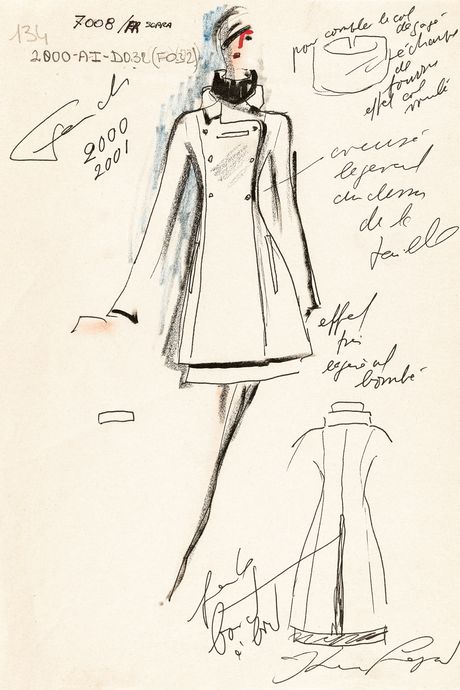

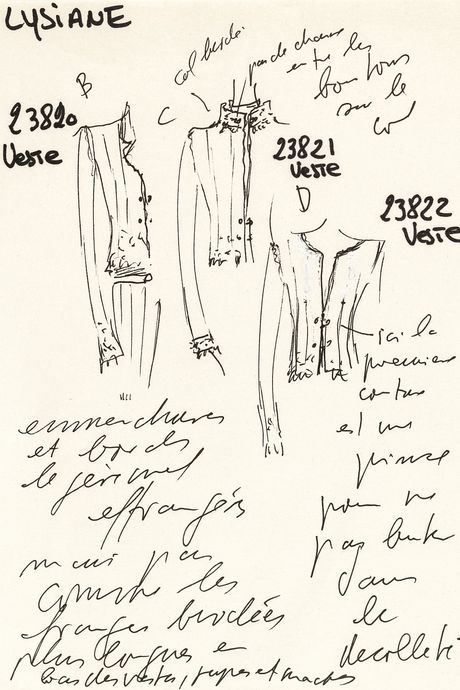

Bolton’s aim was to find the “Karlisms” in his designs for the different houses, and his method was Lagerfeld’s sketches. He was one of the few modern couturiers who actually sketched, as unbelievable as that sounds. He developed the childhood skill when he moved to Paris in 1952 from his native Hamburg. He sharpened his skill under fire as a junior assistant at Balmain, where he was required to make sketchbooks, in detail, for buyers and clients. As he once said of couture in those grim, postwar years, “I thought the backstage atmosphere was terrible. But I said to myself, ‘You’re not here as an art critic, you’re here to learn, so shut up and look.’”

For Lagerfeld, who in later life would begin his day sketching at home, the drawings were at once a mode of expression, Bolton noted, and of communication. Bolton said he got the idea for the exhibit from watching Lagerfeld talk to his premières d’atelier, or chiefs of the workrooms, who would take his illustrations and turn them into three-dimensional garments. He worked with many of these individuals for decades.

“He would call them the architects of his vision,” Bolton said. “What I found impressive was the simplicity, the seeming simplicity, of what they were doing. They talk about it in such simple ways — like they’re just buttering a piece of toast. In fact, it was sophistication.” I know what he means. One of the delights of being in his studio was watching him jump up from the desk and fall into a discussion with a première over a seam or a shoulder. Their exchange was so intimate and knowing and without apparent hierarchy. Then Lagerfeld would return to the desk and talk about something superficial.

For the first time, the Costume Institute has included video interviews with five of Lagerfeld’s premières — among them, the artisan Nicole Lefort, whose workshop created astonishing hand-painted designs for Chloé. Produced by the French filmmaker Loïc Prigent, the videos will be presented on screens in the exhibit with transcripts printed in the catalogue. Not only do the interviews serve as an important window into Lagerfeld’s creative process, but they also celebrate the craft tradition, at least as it still exists.

Tadao Ando designed his set essentially as a serpentine line intersected by a straight line. Indeed, it’s one of the better costume sets at the Met because the intersecting lines create openings in the walls that allow you to see into another section, or another theme, thus treating Lagerfeld’s aesthetic interests equally. Bolton borrowed the basic idea, as well “a line of beauty,” from the painter William Hogarth’s 1753 book The Analysis of Beauty. He then organized the designer’s work around nine “sublines,” using dualities like masculine/feminine, historical/futuristic, and figurative/abstract. In addition to clothes from the Chanel, Fendi, Chloé, and Lagerfeld archives, Bolton included a black coat from Lagerfeld’s 1958 debut collection for Patou and a new version of the coat, with the décolleté in the back, that he did for the 1954 Woolmark Prize. He was one of three winners, along with Saint Laurent. Balmain remade the design for the exhibition.

“I hope people come through and really focus on the detail,” Bolton said last week. “Because sometimes people dismiss Karl because he wasn’t as dramatic as, say, John Galliano. But the refinement and delicacy of these pieces is just extraordinary.” Lagerfeld’s work is certainly a head trip, stuffed with so much knowledge (the exhibit will include images of his references on many of the displays) and, at the same time, as light in feeling as haute couture is supposed to be.

One of the knockout looks in the show, from Chanel’s 2003 Métiers d’Art collection, is an ivory silk, cashmere knit and tulle suit embroidered to look like the fabric and surface bits are disintegrating. I remember when Lagerfeld explored this technique — call it post-deconstruction. “Nine out of ten people who’ve come through this show comment on that look,” Bolton said. “Because it’s so simple and light.” And yet not. It is a mystery, like a pair of fur coats from Fendi in 2001, one inspired by a color chart and the other made of pieces of shaved mink assembled into a complex geometric pattern, inspired by Sonia Delaunay’s paintings.

Ultimately, what these and other “Karlisms” have in common is a certain Karl silhouette. You see it in the line of the disintegrating suit jacket and the Fendi coats — a line that curves distinctly inward from a rather high armhole. “This obsession with that part of the body — which he would return to again and again,” Bolton noted, “it’s really a boy’s body.” It’s also, in a way, a 1920s body, a form that was a touchstone for Lagerfeld and one that also surfaces in Coco Chanel’s early, superlight tailoring. Either way, it’s about youthfulness.

And it shows that his approach was far more consistent than it might appear. He didn’t want the world to see him that way, just as he didn’t want to come across as hardworking. “Catch me if you can” might have been Lagerfeld’s motto for life.

More From Fashion's Biggest Night

- Jameela Jamil Isn’t a Fan of This Year’s Met Gala Theme

- Teyana Taylor Snuck Chicken Nuggets Into the Met Gala

- Met Gala 2023: All the Looks