A lot of things were hiding in Jun Takahashi’s clothes. Takahashi, whose label is appropriately called Undercover, brought us up to a windowless floor of a building in Paris that had been stripped to raw concrete, with grainy lighting like a sepia-tone image and some old chandeliers tipped on their sides down the center as if left behind by a former tenant.

So the atmosphere was set for the music, from Wim Wenders’s 1987 movie, Wings of Desire, about two angels who can hear what humans living in Berlin are saying and thinking, their distress from living in a city divided by the Wall and which still felt the damage of the Second World War. The models who opened the show wore gray-and-off-white suits and dresses — again, sepia tones — and every look had a second memory layer of black georgette. You could sort of make out the details of a suit through the veiling — was it a patchwork of fabrics? Was that a playing card near the hem of a jacket, trapped behind the filmy black? — and, in another way, the base layer was erased and transformed into something new.

The sense of being stuck in the world came through in this extraordinary show — that and how artistic expression can somehow release you. This is a condition that many people feel at the moment, and some designers have expressed it with a craving for joy and beauty. On Wednesday, vibrant colors and flowers surfaced in the Balmain, Marni, and Undercover collections. But only Takahashi expressed this desire without banalities. He left its mysteries intact. Hence the veiling.

He said afterward that he saw the collection as a mental reset, and he turned toward the art of Neo Rauch, the German painter whose hard-to-define style often includes surrealist figures against a social-realist, industrial background. As the writer Thomas Meaney said of Rauch’s paintings, they are “ostensibly narrative scenes in which the narrative is stubbornly elusive.” They could strike you, at a distance, as German fairy tales. Yet approach them and the dream dissolves. Takahashi used Rauch’s work for prints for a blouson jacket, a chiffon scarf-layered coat, and a particularly beautiful, floaty dress in a fuchsia-colored print. We’ve seen designers incorporate artists’ work, but Takahashi seemed unusually sensitive to how Rauch’s art would be represented. It was in another class.

He said that a number of friends and acquaintances have recently passed away. So perhaps, in a way, this show was a requiem. But it wouldn’t have been nearly as complex and powerful if the show were only about loss. There were moments — the opening tailored looks — when this modest and often underrated designer broke through the form and did in fact create something that looked new. He ended with a group of dresses whose transparent bubble-shaped skirts were terrariums of flowers and plants, illuminated by hidden lights, and alive with actual butterflies, waiting to be released again.

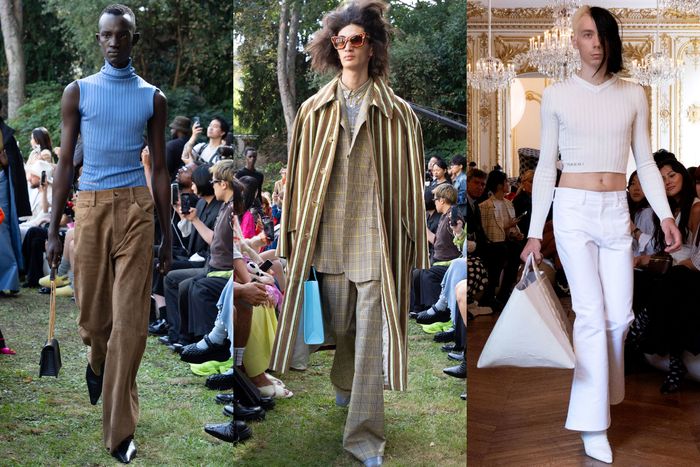

“This is work and work and work that to me is required to understand the pleasure of what we do,” said Francesco Risso before his ecstatic Marni show as he touched flowers made from pieces of tin cans that his studio team in Milan painted and wired into 3-D dresses. He added, “I’ve been thinking a lot about the word joy. It can be banalized, but actually it takes work to act toward that joy.”

Although at times the results felt a bit heavy-handed, as when Risso piled on oversize coats in canvas — one completely embroidered with flowers taken from illustrated books and pasted onto canvas bits — that feeling of pleasure nonetheless beamed through. Some of the best looks were sheer, minimalist dresses (barely a slip) and knit jackets, skirts, and pants in stripes with surprising structure, considering they were pliable knitwear.

He showed the collection in Karl Lagerfeld’s former house on the Left Bank, a sprawling mansion with a garden. But even if one had been in the house before, when Lagerfeld was alive and hosting a lunch or giving a party on the ground floor, it took a lot of memory to summon a connection. It was essentially an empty dwelling.

“The Balmain garden,” trilled Olivier Rousteing, with his new long braids, before his show on Wednesday night with Cher in the audience. Unlike some designers at heritage houses, Rousteing isn’t complacently tweaking Pierre Balmain’s sunny femininity. He digs deep every season, putting a lot of himself into the designs, and though Rousteing’s style is not my thing, I appreciate what he does and his rigorous savoir-faire. His clothes are incredibly feminine this season, close to the body and almost a little distorted, as if influenced by social-media images. Skirts are carved over the hips, bustiers rounded over the breasts for an exaggerated effect, and everything is soaked in spring colors, with polka dots and flowers — some fashioned from recycled plastic bottles. It was quite an intense and personal garden, as you’d expect from Rousteing.

By contrast, The Row was rather drowsy and reclusive looking as Mary-Kate and Ashley Olsen sent out maxi T-shirts and oversize coats with what looked like cotton toweling tucked into the neckline and models occasionally in white bedroom slippers, as if fatigued from too much fashion. The Olsens’ reliable tailoring looked fine, as did the T-shirt dresses — echoes of their early collections — but the many rain ponchos and wrappers, not to mention the hotel slippers, seemed a retreat. You’d like a bit more from them.

Dries Van Noten, who has a fantastic private garden outside Antwerp, stuck to familiar sportswear styles with a menswear versatility, like khaki and denim separates, blazers in different proportions, striped shirt dresses, and rugby shirts, and then reworked them in fresh ways. It was a great hustle without the sweat.