On the way to the Louis Vuitton men’s show, on one of those tour boats plying the Seine, a friend remarked that a passing boat probably belonged to the House of Chanel and it was racing to get its guests to a show before ours.

It was a fine joke. Chanel wasn’t doing a show, of course. But fashion houses are in a race — for attention, for profits, to signal their relatively newfound inclusivity and, thus, their virtue. Hardly a week goes by without an event somewhere, preferably at a historical site. Vuitton was just in Greece for a jewelry presentation at the Acropolis; before that it was in Seoul for a women’s show on a bridge. My dream is to one day be invited to the back of beyond — say, far West Texas or the Badlands — for a show where the terrain and light are truly connected to the fashion and might provoke an emotional response. But, of course, that would require an actual concept — not merely the complacent belief that if a luxury brand stages a spectacular, with stars, then it must be good.

Still, the watery approach to the Vuitton show on the Pont Neuf — the oldest and most celebrated bridge in Paris — was novel. In nearly 40 years of coming to Paris, I’ve never ridden a bateau mouche. We set off at 8:40 p.m., from a dock near the Musée d’Orsay, for a show that was to begin at 9:30 p.m., though it went on much later — to the irritation of people on social media. This was, after all, the highly anticipated debut of musical artist Pharrell Williams as Louis Vuitton’s new men’s creative director, succeeding Virgil Abloh. It was also the first major test (barring the 2010 disaster of Lindsay Lohan at Ungaro) of whether a person successful in other creative fields could lead a big fashion label.

The answer to that question, based on the showing on Tuesday night, is “yes” — and “no.”

Before the show, in an informal interview at Vuitton headquarters — steps from the Pont Neuf — Williams was characteristically sanguine. If he had been competing for the men’s job, he might have had reason to question his legitimacy for the role, he said. “But the difference is I was chosen. The universe lined it up. When you’re chosen, you’ve just got to ride.”

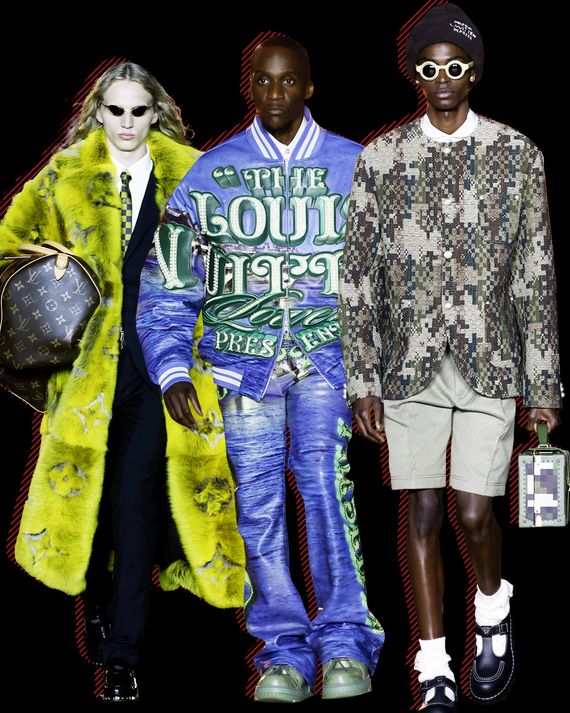

Williams went on to explain, when asked about his vision for menswear, that he worked with the in-house design team to identify seven or eight touch points. These included his personal journey, from his native Virginia to Paris (he did a riff on the state’s tourism slogan “Virginia Is for Lovers” with products sporting the monogram “LVERS”); comfort; sports; his version of dandy dressing; a deep dive into Vuitton’s Damier check pattern; and a collaboration with the artist Henry Taylor, whose artwork became the basis for microembroideries of garments.

“LV is for Louis Vuitton, but it’s also lover — like a lover of life, a lover of opportunity, a lover of this moment,” Williams said expansively. “In fact, when I got the appointment, it was very clear the sun was shining on me, and on my team. And the question is, ‘Are you a lover of life … of expeditions …’ And if you are, we’re going to design for that.”

In other words, Williams is designing for the consumer or, to put it more plainly, for the consensus of opinion around what consumers want today. And that is not a very demanding place for a brand like Louis Vuitton.

To be sure, Williams and the folks at Vuitton staged a spectacular show: 1,900 guests on the arched Pont Neuf at sunset with additional people watching from their apartment windows and the balconies of the Cheval Blanc hotel (another LVMH property); some 70 models walking on a runway covered beyond the curbs with a gold material that stuck like tape to the pavement and repeated the Damier checks and a VIP roster that included Zendaya, Rihanna (in a jumpsuit unbuttoned to show her baby bump), Beyoncé, and Jay-Z, who later performed.

As a friend of mine, who is a seasoned publicist, said beforehand, “Beyoncé’s here. Rihanna’s here. The world is here. Tonight the richest man in the world owns Paris.” My friend meant Arnault, who was also there.

The overriding impression I had of the show itself was confidence. Williams knows how to do things very well, as you would expect from an accomplished artist and businessman. He unquestionably has many of the skills, perhaps the most important skills — showmanship, team building — for a fashion creative director.

But he needs something more. Call it audacity. Many of the designs, like the Damier-checked sportswear and the pixelated camouflage patterns, were well executed but hardly a test of the imagination, and several looks or individual products seemed an easy repeat of styles or attitudes that have been around for a bit, like the notion of wearing a boxy Chanel-like cardigan jacket with a skirt, crunched-down socks, and modified brogues. Shades of Marc Jacobs? Or maybe Williams himself. He showed varsity jackets, apparently a nod to his high-school years and now embellished. Alas, the style is a frequent flier on the runways. Williams did not seize the opportunity to propose any new shapes, or ways of addressing the body, or thinking about luxury — in short, anything that might challenge assumptions.

One hopes that Williams will find that nerve with time. The thing about great fashion, like all art forms, is that it goes further than most people’s expectations. It should shock us or at least surprise and confound us. Think of the landmark fashion debuts in recent times — John Galliano at Dior, Martin Margiela at Hermès, Raf Simons at Jil Sander, Phoebe Philo at Céline, Jacobs at Vuitton (notably after the Murakami and Sprouse tie-up), Demna at Balenciaga. They disturbed the peace. And then the whole fashion business seemed to wake up from its momentary slumber.

Love is fine but, creatively, it tends to wear thin.